Fort Mandan State Historic Site is temporarily closed for maintenance until further notice.

Intro | Frontier Scout | Wales | Trobriand | Surgeon Reports | Marsh | Indian Gardens

Introduction | Diary

Excerpts from the Diary of General Regis De Trobriand at Fort Stevenson:

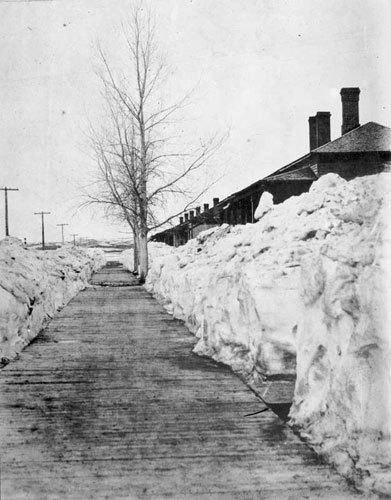

January 6, 1868

[a snow storm made it impossible for General De Trobriand to leave his room. He had a personal cook and a small kitchen attached to his quarters, though, so the cook was able (with difficulty) to prepare both breakfast and dinner. Trobriand’s report on his meal indicates the quality of food available to the commanding officer.] . . . for dinner; second beefsteak, second cup of coffee with milk; but there was a dessert: a slice of peach pie.

January 7, 1868

[the storm continued to reduce the quality of his food to something close to what the enlisted men would eat] From beefsteaks, I have come down to the simple slice of fried ham. That is something to make a face about, but when one is hungry, it isn’t hard to eat. But it is quite an abuse of language to call that a dinner.

January 8, 1868

The cow that provides the milk for our table (Mjr. Furey’s and mine) is in the old office of the adjutant, and my old lodging shelters a half dozen cud-chewers.

February 11, 1868

. . . dinner doesn’t take long. Little time is required to eat soup, a piece of beef or rabbit, some canned vegetables (we don’t have any fresh vegetables, fruit, or eggs), and a slice of pie.…

March 1, 1868

How tired I am . . . of the limitations of fare which because of the absence of fresh vegetables, eggs, fowl, veal, mutton, and even game has reduced us to a diet that brings scurvy to the soldiers and takes the edge off the appetites of the officers. . . .

April 8, 1868

Yesterday, in the afternoon, two of our men died; one from a heart disease complicated by scurvy, the other from just scurvy. This sickness weakened our garrison considerably during the winter and reached its height last month. Right now we have in the hospital thirty-two sick with scurvy, and thirteen more are exempt from service in their company, having only a light touch or just getting over it. In addition there are six employees of the quartermaster who are being treated at the hospital, which makes a total of fifty-one cases of scurvy, equal to one-fourth of the garrison.

These regrettable health conditions are the result of being without fresh vegetables for a long time and of having rations of fresh meat distributed only twice a week. The principal food of the men is salt pork, salt fish; and so there is sickness. Nevertheless, it may be presumed that it would not have reached the proportions I have just indicated if our men had had good quarters from the beginning of winter. Unfortunately the work was begun too late last summer, and as I have related, one of the two companies was not comfortably installed until the last days of December, and the other in the first days of January. Until then they were exposed to the rough weather of the end of November and the whole month of December, with no shelter but miserable edge tents. When the snow and ice came, they dug out the inside of the quarters three or four feet deep, and built themselves small earthen fireplaces, which had the inconvenience of producing stifling heat when the fire blazed and freezing cold when it was out. Moreover, sleeping on the ground wasn’t good for them. Add to this and to the salt rations the constant fatigue from the hardest type of daily work, and it is not wonder that scurvy has been so prevalent, with upset stomachs, tired limbs, and sorely taxed constitution. Fortunately the ordeal is just about over, thanks to the imminent arrival of the steamboats and the supplies they will bring us.

To combat this evil, and especially to forestall it, we have in addition to the usual remedies of the pharmacy, a small, wild white onion, or shallot, tasting very much like garlic, which grows in abundance on the prairie. The Indians gather much of it for us in exchange for small quantities of biscuits, and so the monotony of the usual fare is agreeably and usefully varied by this natural condiment, of which we are all very fond. The Indians supply us with a cylindrical tuber as thick as a thumb, which the Canadians call artichoke, I do not know why, for nothing is less like an artichoke. In form it is more like salsify. Raw, it is almost without flavor; cooked it tastes like a parsnip or like the most insipid turnip [this is probably the wild prairie turnip]. The wild shallot is infinitely preferable. . . .

April 22, 1868

Great activity at the fort [Stevenson]. At nine-o’clock in the morning, the white smoke of a steamboat [the Cora] was sighted above the trees as the point where the hills hide from us the course of the river. Everyone was outside immediately, all glasses [telescopes] were in use, and in a few minutes the movement of the smoke left no doubt. Hurrah for the first boat of the season! [the boat passed on by heading toward Fort Buford.] . . . the servants took back the sacks and baskets as empty as they brought them. They had brought them so they could buy potatoes, onions, and other supplies which they hoped to procure on board. Now the boats will come one after another.

April 25, 1868

Red-letter day. . . . Then around nine o’clock the Deer Lodge came to tie up at the wharf. The arrival of the Deer Lodge enabled us to vary our table menu by purchasing some supplies, with not much consideration as to price. For example: butter, eighty cents a pound; eggs, seventy-five cents a dozen; potatoes, seven dollars a bushel, that is, eleven to twelve cents a pound. Tobacco in proportion.

April 26, 1868

The steamboat Success arrived this morning. Stopped a minute, and not having anything for us, left after an exchange of civilities; a drink and some apples.

July 20, 1868

. . . around noon, clouds of grasshoppers began to show up in the sky. A multitude of these fearful insects flew skimming along the ground, and the layers seemed to thicken as they rose in the air. In the direction of the sun, these innumerable multitudes, more visible to the naked eye, looked like a thick dust of white specks which drifted, passed each other, and multiplied in the air. Finally, the last and fatal symptom, a great murmur like the steady rumble of far away carriages filled the air all around. It was the droning of this traveling ocean of winged insects. Our gardens and pastures would be all gone if this cloud came down to earth. Two or three hours would be enough for complete and absolute devastation; everything would be devoured, and nothing could prevent it.

At this time, a black storm began to come up on the horizon to the north. Heavy clouds mounted one on the other, lighted by brilliant and repeated flashes of lightning, which were followed by rolling thunder, nearer and nearer. The noise of the grasshoppers seemed to be its feeble echo. When the storm came up almost above our heads, blasts of violent wind began to blow in squalls, sweeping everything before them, and great flashes of lightning rent the air. Then all that winged dust which was making the sky white passed over us rapidly. Carried by the storm, it crossed the Missouri, and scattered far out on the plains. Our gardens and pastures were saved, at least this time.

The storm, before reaching its zenith, went east, and swept around far toward the south, where it finally disappeared, without moistening the soil of Fort Stevenson by a drop of rain, although it fell in torrents in other places. Great blasts of wind, fierce bolts of lightning, one of which killed an Indian mule grazing on the prairie; finally, a great roar of thunder; all the storm did for us was to drive away the grasshoppers, but it did not water our vegetables.

July 21, 1868

[grasshoppers returned and again were blown off by heavy winds]. This evening, the gardeners report that only the onions were seriously damaged. The corn is intact, and the potatoes scarcely touched.

March 9, 1869

Scurvy at Berthold has been cut down by the supplies of vinegar I sent. Since then, no one has died and the sick are getting better; I am going to send another cart of sauerkraut and pickles.

Address:

612 East Boulevard Ave.

Bismarck, North Dakota 58505

Get Directions

Hours:

State Museum and Store: 8 a.m. - 5 p.m. M-F; Sat. & Sun. 10 a.m. - 5 p.m.

We are closed New Year's Day, Easter, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day.

State Archives: 8 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. M-F, except state holidays; 2nd Sat. of each month, 10 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Appointments are recommended. To schedule an appointment, please contact us at 701.328.2091 or archives@nd.gov.

State Historical Society offices: 8 a.m. - 5 p.m. M-F, except state holidays.

Contact Us:

phone: 701.328.2666

email: history@nd.gov

Social Media:

See all social media accounts